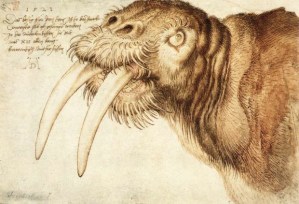

Durer’s Head of a Walrus,1521. Pen drawing in Indian ink and watercolor on paper

Durer’s Head of a Walrus,1521. Pen drawing in Indian ink and watercolor on paper

Walruses are the sole surviving members of the diverse family Odobenidae. Imagine a world of walrus-like creatures!

Odobenus Rosmarus: Odobenus means “Tooth walking.” Circumpolar distribution– Russia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Norway. Uglit is Inuit for a Walrus Haul Out, maybe from the grunting oogh sound they make on the beach and ice when they are all piled up. During mating season, males can utilize beeps, whistles, grunts, rasps, boings and knocks for a “fugue-like love song,” according to Sharon Chester in the Arctic Guide. They also use their tusks for mating displays. After gestation female delivers single calf on pack ice while males haul out on beaches.

Arctic cultures have long hunted walrus for food and hides. Tusks used to make carvings. In 16th century Europeans began hunting them for oil. Except for subsistence hunting by arctic people, hunting is prohibited in the US.

Inuits use penile bone as a club or oosik.

For us, finding walruses began with a two-and-a-half-hour flight by twin engine aircraft from Anchorage, southwest down the peninsula. I lost track of how many volcanoes we passed since I was quite worried Pilot Tracy was asleep at the wheel! Luckily, just when I was about to panic, the scent of smoked salmon filled the aircraft… he must be eating up there–so definitely not asleep! If only I had captured his entrance onto the plane-as Craig sang it later, Moon River…

Lake Clark Air

From our base camp at the foot of smoking Mt. Veniaminof, it was then another twenty minute flight by bush plane (Pilot Tom) or chopper to a black sand beach on the Bering Sea. And from there: a trek across the tundra–and over Hell’s Bluff to the Walrus Haul Out.

The Six Best Places to See Walruses

Pilot Ryan talked a lot about the vastness of the tundra landscape–“like the Serengeti, you can see for miles and miles…”

The Haul Out was BIG! Over a thousand bulls.

“Walruses are coastline embodied. They cannot eat without the sea, feeding a hundred or more feet underwater, where they root beds of clams and benthic worms from the mud. But they must breed and birth in the air. So the herds slide and wallow between, riding the edge of the sea ice south in autumn, then north through the Bering Strait in summer, sometimes leaving the ice to flop onto patches of sandy earth. Like whales, they concentrate rich seas in their bodies—over a ton for females, more than two tons for males. Walruses are not as fat as bowheads; the mussels they eat take their cut of the sunlight. But beneath inches of furrowed skin, a third of a walrus’s body weight is blubber. They do labor no person can, transforming submarine muck into useful tissue and hauling it to shore, drawing a line of energy from the sea onto the solid world.”

— Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait by Bathsheba Demuth

Tough to hike off trail through tundra

The Dream Team: Nancy and Craig, Colleen and Hunter, Chris and Tom and Pilot Leanne (oops, Pilot Tom!)

Lunch on the beach…

Hunter with a whale vertebrae

Craig taking it all in!

On our way, we saw an eagle’s nest too. Pictures here.

Below is Wallace Wildman Martin, from the Anchorage Museum

Happy Ivory Walrus, by Jamie Seppilu, Saint Lawrence Island (Walrus Ivory and Baleen)

“Until the nineteenth century, when the name ‘walrus’ became established, ‘morse’ or ‘sea-horse’ were the most common English terms for the animals. Unlike the creature we now call the seahorse, the walrus does not seem to much resemble a horse, other than in its large size and herd behaviour. But it was perhaps not so much the appearance of walruses as the sounds they made that enabled the comparison. During a voyage to the Arctic in 1789, the writer and anti-slavery campaigner Olaudah Equiano encountered ‘sea-horses’, presumably walruses, ‘which neighed exactly like any other horses’. Vernacular names for sea animals were often maritime equivalents of familiar land creatures, following the ancient idea that all land animals had an aquatic equivalent; thus seals were sea-dogs, the killer whale was the sea-wolf and the porpoise the sea-pig or herring-hog. Some of these nomenclatures, such as sea-lion, elephant seal and leopard seal, survive today. These names were not always consistently applied to the same species; the sea-cow was the manatee and its extinct relative the Steller’s sea-cow, but the term was also sometimes applied to walruses, as was sea-elephant. Other names for the walrus found in early European descriptions include mo-horse, rohart and bête des grands dents, the beast of big teeth. The scientific name for the walrus is now Odobenus rosmarus, which loosely translates as ‘the rosy sea tooth-walker’: in fact this is quite a good description of the walrus, which can look very pink in warm weather when the blood flushes the skin to help the animal cool down. Early observers had correctly identified the walrus as a member of the seal family (although it was also classed as a fish, as was any creature that lived in the sea), and it was with the seals that it was placed when first classified as Phoca rosmarus by the great Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus in 1758. Although there were many good descriptions of walruses, scientists were hampered by lack of access to actual specimens, being dependent on often poorly preserved body parts and the odd short-lived juvenile bought for a zoo. A considerable degree of confusion subsequently emerged within the scientific community about the origins of the walrus, and during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was given a variety of scientific names, including Trichechus rosmarus, Odobenus obesus and Rosmarus arcticus.”

— Walrus (Animal) by John Miller, Louise Miller